Knossos

The Labyrinth of King Minos

Knossos (Κνωσός) is the largest archaeological site on Crete and the most visited tourist attraction also. In the high season you should try to visit the Palace either early or late to avoid queues, crowds and heat. It is open from April to September, daily from 8am to 7pm and from October to March daily from 8.30 am to 3 pm. It lies some 5 km south of Herákleion.

The site has a very long history of human habitation beginning with the the first Neolithic settlement approx. 7.000 BC. But three-and-a-half thousand years ago Knossos was the centre of the island wide, highly sophisticated civilisation of the Minoans. The settlement was by then a monumental administrative and religious centre with a surrounding population of 5.-8.000 people. And even long after the Minoan civilisation had collapsed the town on the site was one of the most important centres of power on the island.

The Palace

The great palace was built and rebuilt between 1.700 and 1.400 BC. The features currently most visible date mainly to the last period of habitation. The entire palace covered 2,5 hectares (6 acres) with 1.300 rooms connected with corridors of varying sizes and direction. There was a theatre, a main entrance on each of its four cardinal faces and extensive storerooms or magazines. Advanced architectural techniques were used to build the palace which in certain parts was up to five stories high.

Palace is perhaps a misleading term. Knossos was not a castle housing a head of state but a complex of interlocking rooms with different functions such as artisans workrooms, storage rooms, oil mills etc. Perhaps Knossos was more like a city in one building than it was a palace in our understanding of the word.

The ingenuity of the Minoans is illustrated by the way in which were able to handle water. Three separate systems were present. Aqueducts brought fresh water to the Palace from springs at Archanes, about 10 km away and the water was distributed throughout the palace via terracotta pipes to fountains and spigots. Sanitation drainage was provided through another closed system leading to a sewer apart from the palace hill. In one room - the Queen's Megaron - an example of the first known water flushing toilet was found. And as the palace hill was periodically drenched by torrential rains, a sophisticated runoff system with channels and basins to control the water velocity was created.

Frescoes and Columns

The Minoan Columns are a distinctive feature of the palace. The columns had a structure notably different from classical Greek columns. Unlike the characteristic Greek stone columns, the Minoan column was constructed from the trunk of a cypress tree. And while Greek columns are smaller at the top and wider at the bottom the Minoan columns are just the contrary. At the palace the columns were mounted on a stone basis and painted red. What can be seen at the site today are, however, reconstructions.

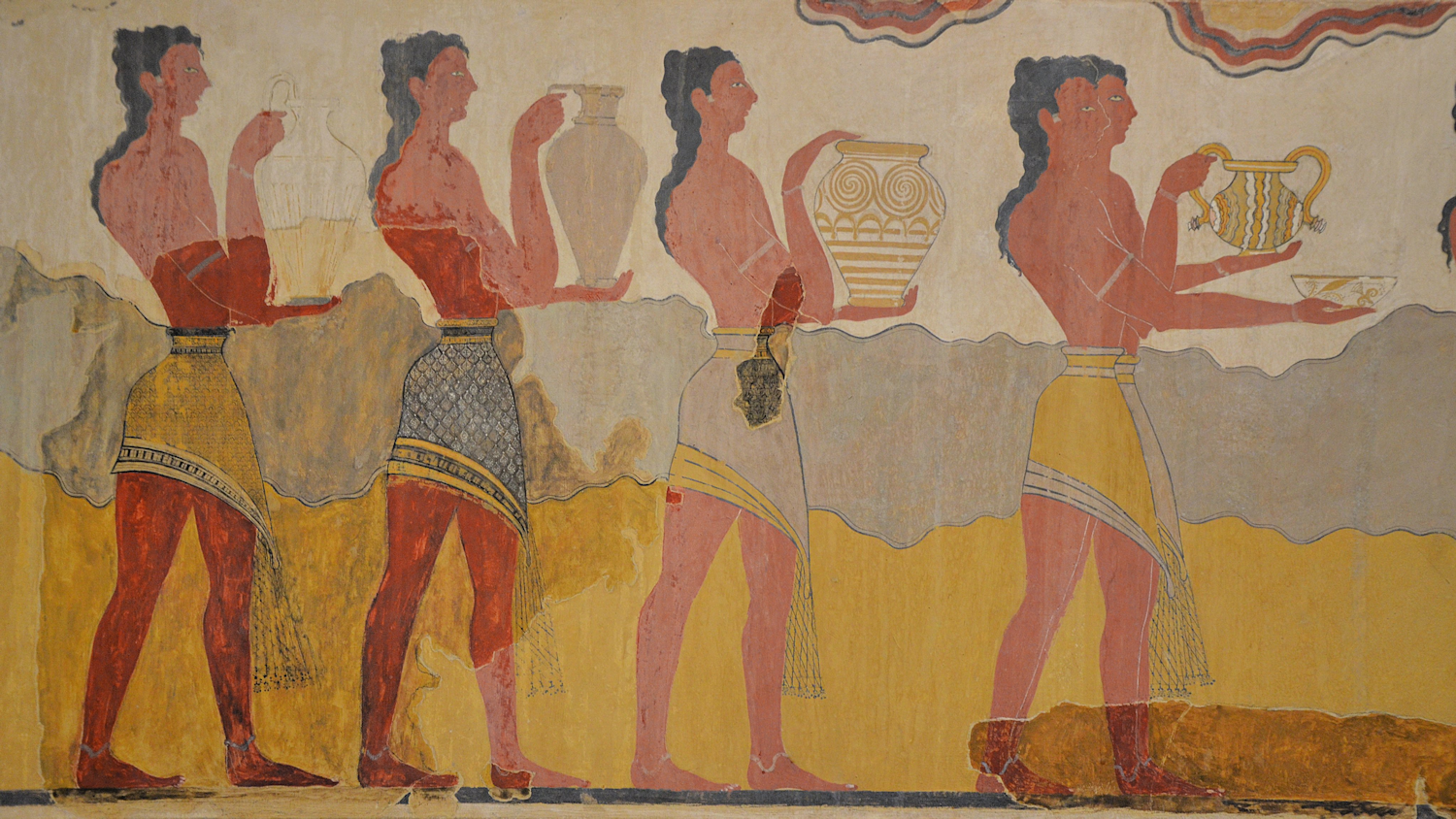

Another remarkable feature of the palace is the frescoes. They are sophisticated, colourful paintings portraying a society which did not choose to portray military themes anywhere in their art. Knossos in general shows no signs of being a military site. There are no fortifications or stores of weapons and the Minoan civilization seems to have been a remarkably non-militaristic society.

Hardly any elders or children are depicted in the frescoes. Mostly it is young men and women engaged in activities such as flower picking, fishing or athletics. Most notably bull-leaping, in which an athlete grasps the bull's horns and jumps over the animal's back. Another interesting feature is the colour-coding of the sexes. Men are depicted with reddish skin, the women as milky white.

Only delicate fragments remained when Knossos was excavated. What you see at the site are therefore reconstructions by the artist Piet de Jong. The original frescoes as well as many other finds from Knossos and the other Minoan sites on Crete are located in the Archaeological Museum of Herakleion.

The Discovery and Excavation of Knossos

The ruins at Knossos were discovered in 1878 by a Cretan merchant and antiquarian by the name of Minos Kalokairinos. He conducted the first excavations, and uncovered part of the storage magazines and a section of the western facade. Several other people attempted to continue the excavations, but without much success until 1900 when an English archaeologist, Sir Arthur Evans (1851-1941), bought the entire site and started conducting massive excavations. He employed a large staff of locals and within a few months he had uncovered a substantial portion of the ruins.

Sir Arthur Evans conducted systematic excavations at the site between 1900 and 1931 and Evans' restoration of Knossos is to a large extend what is seen today. This restoration has been much debated. Critics have called it 'an archaeological Disneyland' saying that Evans used too much imagination in determining the palace's former appearance and furthermore, that due to his heavy-handed reconstructions he has virtually rendered impossible any other scientific interpretations of the findings.

On the other hand, as a layman visitor to the site one must admire the intuition, scholarship and creative imagination of Evans. Whether his interpretations are entirely correct or not they certainly make Knossos an more interesting place to visit compared to the other Minoan sites in Crete, where it is much harder to imagine how they must have looked like.

The Mythical Knossos

Since antiquity Knossos has been suggested as the place of the myth of the Labyrinth of King Minos. An elaborate mazelike structure designed by the legendary artificer Daedalus to hold the Minotaur, a creature that - a monster that had the body of a man and the head and tail of a bull.

The word 'labyrinth' comes from the word labrys referring to a double, or two-bladed, axe. The word is probably not Greek. The labrys symbol had a religious significance throughout the Minoan world and axe motifs can be found scratched on many of the stones of the palace. According to Greek mythology, Minos was a king of Crete, son of Zeus and Europa. Sir Arthur Evans named the Minoan civilisation after him - (but they probably called themselves something else). Perhaps Minos is simply a Cretan word for 'King'.

In the myths, Minos had a son, Androgeus, who won every game in a contest to Aegeas of Athens. The other contestants became jealous of Androgeus and killed him. This then caused Minos to declare war on Athens. However, he offered the Athenians peace if they sent seven young men and seven virgin maidens to Crete every nine years. These were to be sacrificed to the Minotaur.

The Minotaur

This creature was the unlucky offspring of a love affair between King Minos' wife Pasiphae and a bull. The story goes, that before he ascended the throne of Crete, Minos struggled with his brothers for the right to rule. He had prayed to Poseidon to send him a bull, as a sign of approval by the gods for his reign. Poseidon obliged him and let a beautiful white bull rise from the sea.

But Minos had also promised to sacrifice the bull as an offering. However, on seeing how beautiful the bull was, he decided to sacrifice the best specimen from his herd instead. When Poseidon learned about the deceit, he made Pasiphae, Minos' wife, fall madly in love with the bull. She had Daedalus make a wooden cow for her. She then climbed into the decoy to seduce the white bull. The offspring of their lovemaking was the Minotaur. Pasiphae nursed him in his infancy, but he grew and became ferocious. Minos then had Daedalus construct a gigantic labyrinth to hold the Minotaur but apparently they had to feed him now and then and that's where the young Athenians came in handy.

Theseus and the Death of the Minotaur

When the third sacrifice came round, Theseus volunteered to go as one of the 7 young men in order to kill the monster. He promised to his father, Aegeus, that he would put up a white sail on his journey back home if he was successful. Otherwise, the ship would have black sails of mourning.

Now, Minos had a daughter, Ariadne, who fell in love with Theseus as he and the others arrived on Crete. Therefore, she decided to help him. She gave him a ball of thread, allowing him to retrace his path out of the labyrinth. Theseus then went in, killed the Minotaur and led the other Athenians back out again. Theseus brought Ariadne with him from Crete, but abandoned her on their way to Athens. This is said to have happened on the island of Naxos. On his return, Theseus forgot to change the black sails for white sails. His poor father, overcome with grief, then leapt off the cliff top from which he had kept watch for his son's return every single day since Theseus had departed. From this event the 'Aegean Sea' got its name.